These recommendations are in response to the Department of Energy's open RFI re: Input on Potential Office of Nuclear Energy Infrastructure Areas for Competitive Opportunities

Preface: Beginning in 2016, the Department of Energy has had an open Request for Information (RFI) on Input on Potential Office of Nuclear Energy Infrastructure Areas for Competitive Opportunities. Professor Aditi Verma (Good Energy Collective Board member) and Prof. Todd Allen submitted this response to the RFI this spring. Good Energy has long supported the Office of Nuclear Energy in their goal to expand the inclusion of social sciences in their work, and we hope they show interest in the ideas offered by Verma and Allen below.

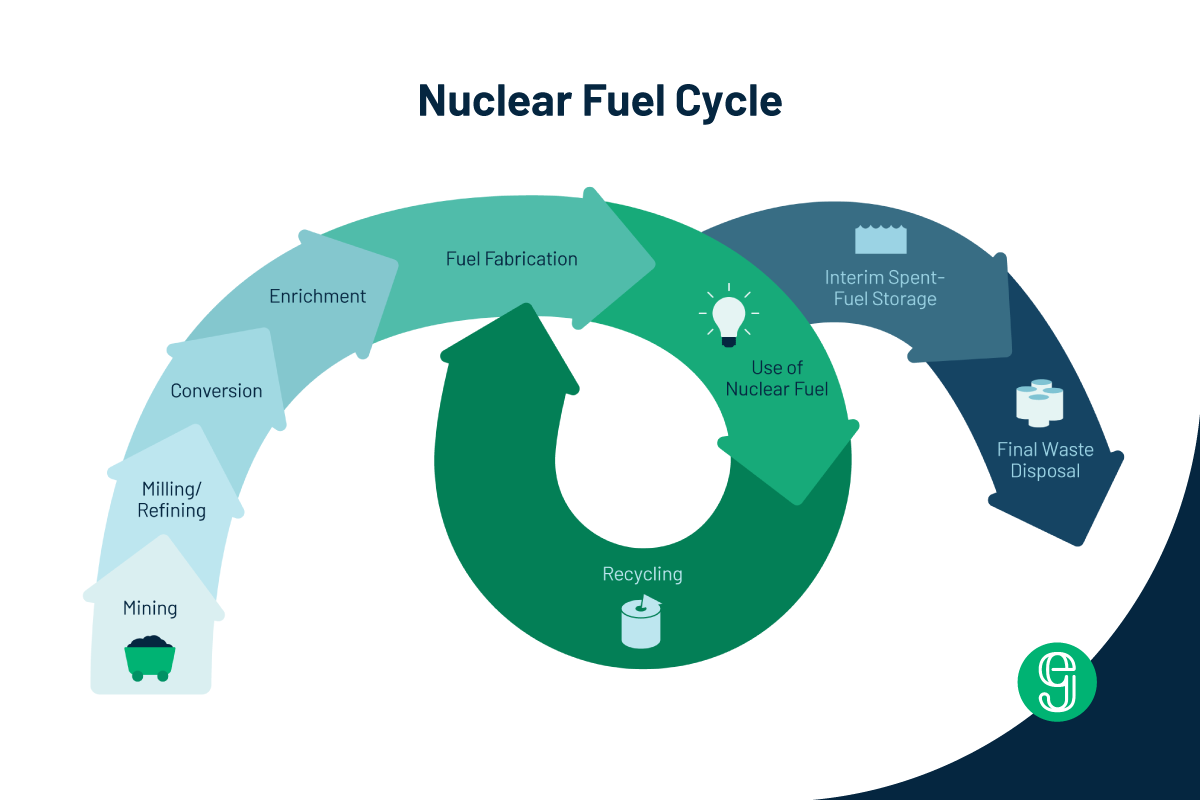

We are excited that the Office of Nuclear Energy has begun to champion a sociotechnical approach to advanced nuclear technology development. We especially appreciate the awards made during the last Nuclear Energy University Program (NEUP) funding cycle to support community-engaged research in Alaska and Wyoming, as well as the IRP led by the University of Oklahoma which seeks to develop a socially led co-design approach for the development and siting of interim spent fuel storage facilities.

Increasingly both national labs and universities are recruiting researchers who bring a socio-technical lens to advanced reactor development efforts, and engineers who have traditionally been concerned with scientific and engineering pursuits are also increasingly acknowledging the need to integrate the social and technical and reaching out to colleagues across disciplines, in particular the humanities and social sciences, to build new intellectual partnerships that have the potential to generate insights that will be vital for the successful and appropriate use of new nuclear technologies. Recognizing the importance of integrating the societal and technical, and in response to advice from our Advisory Board as well as demand from our very own students, we at the Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences Department at the University of Michigan intend to educate future nuclear engineers on the societal, policy, and ethical aspects of nuclear technology development.

All of these developments – DOE-sponsored research funding for sociotechnical research, new interdisciplinary research partnerships, and a growing emphasis on integrating the social and the technical in the education of future nuclear engineers – have, we believe, set the stage for developing a new kind of research infrastructure, one that facilitates sustained engagement with communities.

These ongoing approaches for sociotechnical research and development are a significant step in the right direction and, if institutionalized as infrastructure, would serve as an important signal to both communities as well as researchers who have forged collaborations with communities as well as with interdisciplinary partners that such work is going to be valued by the DOE in the long-run.

Another reason to create such infrastructure is that successful community engagement efforts require relationship and trust-building – both of which are difficult to do over the course of three-year timelines currently prescribed by NEUP funding. As a result, researchers are likely, as part of existing projects, to reach out and partner with communities they are already familiar with. This is both good and bad. This approach contributes to amplifying the voices of communities who have a seat at the proverbial table but it also, unfortunately, perpetuates the marginalization of communities who do not.

To be clear, when we say “communities” – we are referring to communities across at least three scales:

- Potential host communities: these are communities that will host advanced nuclear energy infrastructure. Some of these future advanced nuclear host communities may already host existing nuclear energy and/or research infrastructure such as those represented by the Energy Communities Alliance. These potential host communities are expressing curiosity and interest in nuclear energy technologies and seek both to learn about them and to provide input in the development of the technologies and facilities, as well as key decisions about where and how these facilities will be sited.

- Environmental justice communities: These communities are sometimes referred to as disadvantaged communities. It is important to note that these communities may not necessarily self-identify as such. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that prior generations of nuclear technologies have created both benefits and burdens that have been inequitably distributed. It is important to learn from the experiences of the communities who have disproportionately experienced some of the burdens, to undertake remediative measures, and for the nuclear sector to learn from these past experiences and develop processes and mechanisms for respectful engagement with communities in the future.

- Publics and citizens: the successful and appropriate use of nuclear energy technologies requires the alignment of informed consent across multiple scales of communities. It is important not only for the host community to consent to host a facility but for publics (plural because the public is not a monolithic whole) across the state and across the country also to consent. Consent across these larger spatial scales may take the form of states lifting moratoria on new nuclear construction or a generally positive public opinion of nuclear energy.

We identify at least five main compelling reasons for infrastructure development to facilitate community engagement:

- Making the interface between academia and research institutions porous: The current approach taken by the DOE as well as research institutions to develop sociotechnical pathways for nuclear technology development are framed as research questions, issues, and challenges from the researcher and technology developer’s perspective with a search for community buy-in after the research questions and issues have been framed. A truly sociotechnical approach would be bidirectional – enabling communities to approach researchers with questions and challenges (as they perceive them in the context of nuclear technology use and development around them) and for researchers and technology developers to approach communities (as we are already doing).

- (Re)building trust with communities: We hope that a sustained community engagement infrastructure would help build trust with communities (or rebuild trust where it has been lost), including trust in experts and expertise – which is increasingly strained – often for good reason.

- Empower communities to approach researchers and technology developers: Through a sustained community engagement infrastructure, we hope to empower communities to approach researchers with problems and challenges the communities may already have identified to which advanced nuclear technologies could offer a solution, while also enabling communities to approach researchers and technology developers with any concerns they might have about nuclear technologies. Identifying these concerns early in the technology development process would make it easier (and potentially much less resource intensive) to address vs. in the later stages of technology development when major design changes have ripple effects throughout the design of a complex system.

- Do research with communities, not on communities: A sustained community engagement infrastructure would enable us to undertake research and development with communities, not on communities, which we are now in danger of doing. There is a fraught history, particularly in the context of Native American and Indigenous communities, of extractive research projects that have mined indigenous knowledge as data, often without appropriate recognition and compensation. We should take every measure to ensure that our sociotechnical research efforts generate useful knowledge for communities and technology developers alike. This could, for example, take the form of project outputs including peer-reviewed publications as well as community-facing outputs such as newsletters, museum exhibits, art installations, archives, or other formats that are compelling and accessible to a broad range of audiences.

- Facilitate citizen science and engineering: Finally, many (if not all) advanced nuclear technologies now being developed were dreamt up and invented in companies, universities, and national labs as research problems framed and solved by nuclear engineers. We are of the view that allowing community and citizen input to the technology development process could further open up the design space and possible applications of these technologies by allowing communities to envision and explore whether and how these technologies or other variations of them we have not yet imagined, might offer solutions to problems communities are grappling with.

Given all of the above, we would like to offer a few preliminary propositions for what form the community engagement infrastructure could take.

- A Hub approach: As noted above, communities span at least three scales – the potential host communities, EJ communities, and broader publics. Different approaches, across scales will likely be needed to engage with different forms of communities. What is clear is that these efforts will need to be both local as well as more diffused – polling, online engagement platforms, and content analysis of news and social media, to name some. We believe that a potentially successful strategy could entail the creation of several local ‘hubs’, with hubs working together to create diffused engagement approaches. Initial hubs could be hosted by national labs, universities, and community groups (such as the Energy Communities Alliance) that already have strong partnerships with one or more communities. Future hubs could be competitively awarded in a manner that creates broad regional representation. The hubs could operate in a user facility model, being available for researchers executing typical 3-year grants, allowing continuity with communities despite the periodicity of research projects.

- New infrastructure + repurposing existing infrastructure: The community engagement hubs could repurpose existing infrastructure and/or create entirely new infrastructure, as appropriate. For example, existing research infrastructure at national labs and universities could be opened up to local communities by creating a visitor center, science exhibits, or other community-facing facilities. These community-facing facilities could serve both engagement and educational purposes. The hubs could serve as physical space for convening focus groups to carry out participatory socio-technical readiness assessments of advanced nuclear technologies (data to be linked below once public), function as maker spaces that give communities access to design and fabrication tools, as well as researcher-assisted access to cutting-edge technologies, and finally, the hubs would also serve as support and coordination centers for sociotechnical projects embedded within communities (for example, the NEUP sociotechnical projects NE has already funded). As concrete examples, the Idaho National Laboratory could host a Mountain West hub that combines elements of NRIC facilities, the GAIN Program staff, the CAES CAVE for visualization and the laboratory outreach staff. Michigan could host a Great Lakes hub combining elements of the virtual reactor visualization lab, the Fastest Path to Zero staff and siting tools, the systems analysis tools of the Center for Sustainable Systems, and the outreach networks of the Economic Growth Institute and Ginsberg Center.

- Beyond funding cycles: A central feature of the community engagement infrastructure is that it will allow community-researcher partnerships to transcend three-year funding cycles. While hub-supported projects could certainly span three (or more) years, researcher-community engagement will not hinge on these time-bound projects. The existence of the hubs could enable communities and researchers to engage early with each, assess the project, team, community, and technology ‘fit’ before project proposals are formally submitted to NE. These pre-proposal engagements could set up projects for success. Additionally, the hubs could support NE in reviewing community-engaged research proposals as they come in.

We have laid out some initial ideas for creating new community engagement infrastructure under the auspices of NE. We believe that such infrastructure if created, would strengthen our ability to create truly useful and socially desirable technologies. We would be happy to engage with NE in future conversations about creating such community engagement infrastructure.

.png)

.png)

%252520(1200%252520%2525C3%252597%252520800%252520px).png)